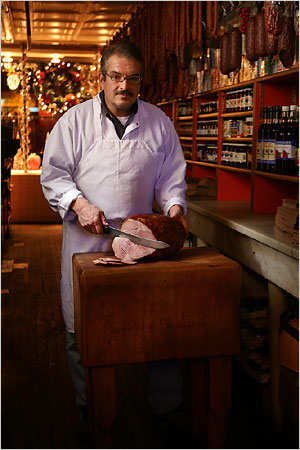

We get an e-mail from Jerry at 8:00 a.m. Wednesday morning that reads "Hey Kids, Check out the Dining Out section in today's NY Times." OK, modest message -- probably somewhere inside. Living and working in Jersey, I read the paper after dinner. Get home and wow! Jerry's on the front page, slicing ham. Good picture, too (see repro to the right of this post; photo by Tony Cenicola/The New York Times). "Fanfare for the City Ham, a Country Cousin" screams the headline. The

Web version's editors chose Baczynsky for their lead image.

Here's the story, by Matt Lee and Ted Lee:

December 20, 2006

Fanfare for the City Ham, a Country Cousin

By MATT LEE and TED LEE

TO Southerners like us, the apotheosis of pork is country ham — the hind leg of a pig that has been immersed in rock salt, hung in a smokehouse, then aged for many months to prosciutto-like firmness. We have hallowed country ham in national magazines, clucked over the decline of its mostly artisanal production and driven close to a thousand miles for a particularly fine Kentucky specimen. We have spent more on these hams in some years than we have on health insurance. We’ve even given them as wedding gifts.

So our dirty little secret, the one that may cost us our invitation to the next Southern Foodways Symposium, is that we are not, in fact, pork purists: we’re suckers for a glazed baked ham, those brine-plumped, brown-sugar-encrusted pork bombs that anchor the buffet line in all 50 states at this time of year. Their rosy sheen, firm salt quotient, flaky texture, sweet edge and bacony, clove-scented flavor invariably bring us back to the table for thirds and fourths. There, we’ve said it: we love regular baked ham.

We were surprised (and perhaps even vindicated) by our recent odyssey through the best of New York City’s homegrown hams — city ham, if you will. Where a country ham might be cured for weeks in dry salt, then smoked, then aged for a year (or two), city hams seem like a shortcut. They are soaked in or injected with a brine of water, salt and sugar before being cooked and then smoked for a few hours. The whole process may take less than two days.

As you might expect, there are differences in taste and texture, too. Country hams have the leathery texture of serrano ham and an earthy flavor that comes from long aging. But in many cases, the New York hams we tasted — and we sampled more than 25 of them, from 10 producers — delivered pork sensations every bit as nuanced, rich and magnificent as their country kin.

Tucked away at the back of meat markets that blend in with storefront real-estate agencies and baby boutiques or in low-rise industrial buildings in residential neighborhoods, the smokehouses of New York City tend to be invisible, their secret discernible only upon stepping through the front door and deeply inhaling. And, in fact, some producers seem to prefer it that way.

“I don’t show anybody what we do,” said Jerry Kurowycky (pronounced kur-VITZ-kee), the owner of Kurowycky Meat Products, as he ushered us past refrigerator cases of hot mustard and Polish butter at the front of his store, on First Avenue in the East Village. “But I’m happy to give you a general idea.”

So we followed Mr. Kurowycky, who on a balmy December day wore shorts and flip-flops, through a narrow passageway to a tiled preparation area with a brick floor. Recessed into the back wall were four soot-black smoking chambers with heavy iron double-doors. A shovel leaned against a large paper bag of hardwood chips at one end of the room.

Mr. Kurowycky, whose grandfather Erast bought the store from a former employer in 1955, claims he makes hams exactly the way his grandfather did in the Ukraine before World War II, by hand-rubbing fresh hams with salt and sodium nitrite, then letting them cure in pans for two weeks. He then rinses them, cooks them for six hours, and hangs them in the smoker overnight. Finally, they are glazed with brown sugar. “But that’s strictly for decoration,” he said.

Mr. Kurowycky’s ham may be unique among the city hams we sampled for its dry cure; most cured hams today are immersed in or injected with a liquid brine, which speeds the process.

Indeed, his ham appeared a shade drier and more muscular than the wet-brined New York City hams we tasted, but its silky texture and prominent smoke flavor stood out, too. It had a decent layer of fat and some marbling, with a sweet nuttiness, and an appetizing but unobtrusive saltiness.

A couple of blocks away, the East Village Meat Market brines and smokes its top-selling hams. Boneless ones, labeled “off the bone,” sit in a refrigerated case ready to be sliced by one of the stern countermen in smocks and blue paper hats; toward the back of the store, on a stainless steel table, under the glow of fluorescent lights, are the prized whole hams.

On the day we visited, the market’s owner, Julian Baczynsky, 81, a diminutive man with silver hair and thick spectacles, sat in a chair watching over them. He let Andrew Ilnicki, the market’s manager, do the talking: these hams soak in their salt solution for two weeks, hang in the smokehouse for 12 hours, and are then glazed a burnished brown with caramelized sugar. The process produces a ham that looks and feels wetter than Mr. Kurowycky’s, but has a big, well-rounded flavor, with some creamy fat in each slice and an oily smoke flavor toward the edge.

(To confuse matters, two years ago the market began selling a product labeled City Ham, a smaller, boneless ham using two loinlike cuts of the leg. “Everyone’s watching their diet now,” Mr. Ilnicki said. “There is no fat on this ham. Among young people, it’s very popular.”)

We took the elevated M train to Karl Ehmer Quality Meats, a factory-scale smokehouse in Ridgewood, Queens, where we were allowed to witness a brining up close. (Another large-scale operation in Queens, Schaller & Weber, is in Astoria, but its retail flagship is on the Upper East Side.) Karl Ehmer, the company’s founder, opened his first store in Manhattan on East 46th Street in 1932, and moved the operation to Queens in the 1940s. His grandsons now run the business, which supplies the retail market at the front of the building and specialty food stores around the Northeast.

This is the largest of the smokehouses we visited. The aqua-tiled cold room where the brining takes place could have contained both Mr. Kurowycky’s and Mr. Baczynsky’s entire operations. It prides itself on being the only smokehouse in the area to brine its hams using an artery pump, a steel water gun with a sharp needle for a barrel that delivers the cure (a solution of salt, water and corn syrup kept at a constant 34 degrees) to the ham through a hose hung from the ceiling.

We watched as John Ahrens, a butcher at the company for 28 years, poked the needle into the main artery at the hock end of a plump ham resting on a stainless steel scale, then pulled the trigger. The ham appeared to inflate as it absorbed the cure, and the red digital readout on the scale ticked higher. After the pump treatment, each ham is brined overnight in a large tub. From there it is hung on a rack in the smoker, where it will cook and absorb smoke for a total of 18 hours before being rinsed, cooled down and vacuum-packed.

The whole bone-in Ehmer hams we tested had a well-balanced ham flavor and were moderately salty, with an inflection that reminded us of our cherished country hams. A brown-sugar-based glaze on this kind of ham is ideal.

What is perhaps the most unusual cured ham operation in the city takes place about a stone’s throw from the 6:08 to New Canaan, Conn., at Koglin Royal Hams, in the Grand Central Market. Armin Koglin, the proprietor, is for the most part a curator, importer and retailer of others’ hams, but with some regularity he cures his own, on-site, in three different styles.

In his walk-in fridge the hams are boned and tied in butcher’s twine, then soaked in brine for a couple of days in individual buckets before being coated with spices, mustard or honey (or all three) and baked.

His Austrian Kaiser Ham, with the unmistakable scent of caraway seeds, has a faint herbal character on the palate, the gentlest impression of salt and the delicate porkiness of a fine broth. This subtle ham will not benefit from further glazing or baking and should be eaten without the distraction of bread, cheese, mustard or mayonnaise. This may be the ham that persuades you to add cold pork and lager to your breakfast repertory.

A more freewheeling style of ham — intensely smoky but no less delectable — is found in abundance in Brooklyn, at Jubilat Provisions, a small, family-run shop in Park Slope, and farther north, at a collection of Polish smokehouses in the heart of Greenpoint. Outside Polam on Manhattan Avenue on a recent Saturday afternoon a scrum of teenagers blocked the door, chomping on lengths of landjäger (a handmade, cigar-size alternative to the Slim Jim).

Inside, the crowd was three deep at the counter, with no apparent line or take-a-number system. We waited a while, then bolted, crossing the street to the W-Nassau Meat Market, where ranks of steel hooks hung with sausages marched across richly seasoned bead-board walls. Jolly counter folk in red smocks and matching newsboy’s caps tended to an orderly line of neighborhood grandmothers and men covered in Sheetrock dust that stretched the length of the counter, doubled back past shelves of red currant preserves and jarred beets, to the door.

It’s a serious place with a serious clientele. The line moves quickly, so you’ll want to know what to order. Here’s all you need to say: “Smoked cooked ham.” Theirs has a robust piggy flavor and the impression of sweet fruitwood smoke, mild salt and a voluptuous layer of tasty fat.

A few blocks south and west is Steve’s Meat Market, a smaller place and the friendliest of the lot, with a couple of young countermen in baseball caps offering samples and bumper stickers. The larger cut, simply called boneless, is the one with the most interest: a richly peaty smoke flavor with herbal undertones that seem distinctly Southern.

We stood in line for a few minutes while the cashier totaled the purchases of a woman in an ankle-length fur. The cashier reached across the counter to hand the woman a bulky shopping bag, then another, then a third, and finally a fourth.

“Sorry,” she said to us. “I drive in from Jersey, so I’ve got to load up.”

“Shopping for the holidays?” we inquired.

She looked at the bags, lifting them slightly. “No,” she said. “I’ll be back again before then.”

(Copyright 2006 The New York Times Company)

Any body else out there a fan of Kurowycky's? I bet his phone was ringing off the hook today.